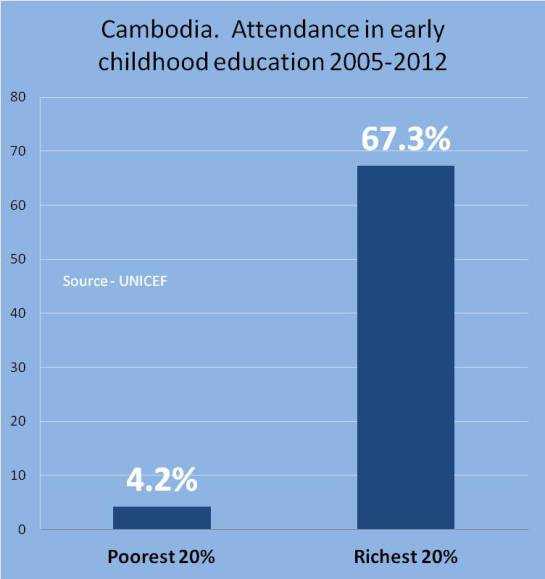

Mind the gap. Two thirds of the infant children of Cambodia’s wealthiest 20% will attend pre-school.

One of the first impressions I had of infant children in Cambodia was formed in 2004 when I first visited Siem Reap. Each day as I travelled to and from the Angkor temples – I had a wonderful guide named Joe Topp – we would pass small villages and farmhouses, and standing outside these places were young children, listless, just watching the world go by.

Their blank faces haunted me: these children seemed somehow disengaged from the world around them: I realised I saw very few children actually playing. They weren’t pushing toy trucks through the mud, or sploshing merrily by the pump – they were just standing there.

In a couple of posts recently I have talked about pre-school education, and I was rightly critiqued by one reader who reminded me that early childhood education isn’t simply a matter of formal classroom interventions, but is a whole process of socialisation and engagement – very often through play.

So I wondered if there were any figures around this usually elusive topic. UNICEF is where I started, and sure enough I got from their website the figures which populate the chart above. Here, they compare the likelihood that young children from the poorest 20%, and from the richest 20% of Cambodian families – will attend formal early childhood education.

Yes, but what about toys or books? After all, one could have a perfectly fantastic upbringing in a home where children are encouraged to take part – for example in the way my mother used to encourage us kids to get involved whenever she was making biscuits. We were given the task of cutting the dough into shapes.

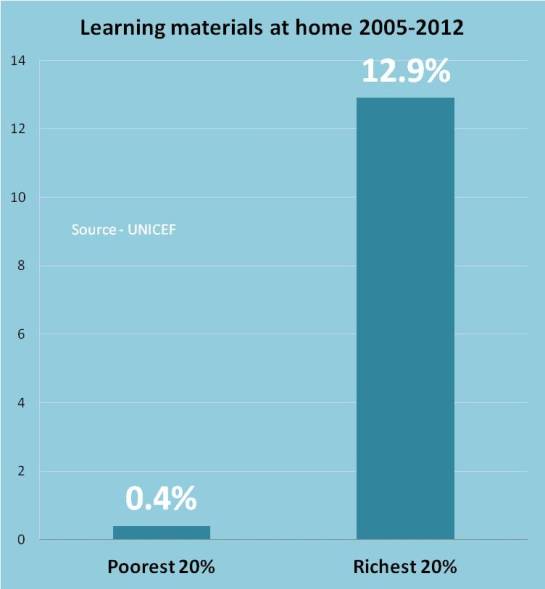

Well, here’s one indicator; again from the UNICEF website. Below, we compare the presence of books and learning materials appropriate for young children in the homes of the poorest 20%, versus the homes of the richest 20% of Cambodian families.

Here the gap (12.5%) isn’t so wide, partly on account of the fact that so few of any Cambodian homes have learning materials suitable for the youngest members of the household. Only one relatively wealthy home in every eight has such materials available for their young kids.

The UNICEF surveys also asked about playthings, and here the figures are somewhat better.

- Some 30% of the poorest 20% of households have playthings at home for the children.

- Of the richest 20% of households, those with kids that is, some 57% have playthings available for their children.

Perhaps the gap doesn’t sound so bad – but what this still means is that 7 out of every 10 children in poor regions don’t have toys.

I would caution readers who take this as an open invitation to flood Cambodia with just any old toys. Toys should be sturdy, versatile, educational and encourage imagination. In Phnom Penh, the day after I visited S 21 I happened to walk past a toy store which seemed, unfortunately, to specialise in plastic replica guns. These looked like the real thing, and it struck me what a wicked thing to encourage kids to play with – especially for the generation born within years of the National Holocaust.

- For a whole host of UNICEF statistics – click here.

- For more on Primary School resources needed for rural Siem Reap.

You must be logged in to post a comment.