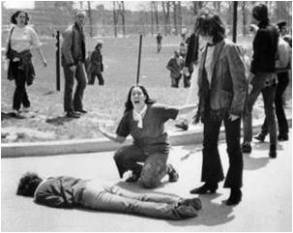

John Filo’s photograph of Mary Ann Vecchio, kneeling over the body of Jeffrey Miller minutes after he was shot by the Ohio National Guard. The protest was over the bombing of Cambodia.

By 1970 public sentiment in the USA toward their war in Vietnam had turned almost decisively. In late 1969 the spotlight had fallen on the My Lai massacre in which a village of innocent people were murdered by out-of-control US soldiers. There was no moral defense for this. The war was increasingly unjustifiable – except to the so-called political Hawks who saw Vietnam as the place where the communist dominoes would be stopped from falling (into Thailand, Cambodia, Malaysia, Indonesia.) Now on April 30th 1970 President Richard Nixon announced to America that, in fact, he was extending military action into Cambodia.

In fact the US had already been actively bombing the eastern parts of Cambodia, adjacent to Vietnam. This was Nixon’s “secret war” urged on by Henry Kissinger (three years later recipient of a Nobel Peace Prize.)

The announcement on April 30th spurred a planned demonstration by peace protestors across dozen of university campuses including Kent State University in Ohio. Here on May 4th 1970 the protestors were met by the National Guard who, under specific orders, aimed and fired their rifles at incredulous protestors. (Witnesses thought surely they were using blanks.)

Four students were killed.

The photo (above) was taken by a passer-by and widely published. Of all media images this is the one that took the horror of the Indo-China conflict right onto America’s own doorstep. Days later, fuelled by singer Neil Young’s anger over the event, Crosby Stills Nash & Young released the single Ohio which to me, even 44 years later distils the feelings I have toward wars in general.

Alas, the photo has echoes today, not in the USA so much as in the Freedom Park of Phnom Penh where Hun Sen’s soldiers have killed protestors seeking fair elections and living wages. A common element when I look at the photos of both events is that the soldiers are masked. The Ohio National Guard soldiers were wearing gas masks – their use of teargas was not successful because the breeze dispersed this – while the Cambodian riot police wear motorbike helmets.

I wonder if this is for physical protection or whether it reflects the shamefulness of meeting a peaceful protest with unnecessary brute force.

You must be logged in to post a comment.